Revolutions followed the invention of the printing press. And war. Millions were killed. Many more were uprooted and dislocated, their places in ruins. Entire systems of belief and governance were torn down before anyone knew how to replace them. The printing press didn’t create order; it created possibility, and with it, chaos.

It took centuries for new institutions to emerge that could manage this new world of ideas. Universities, newspapers, parliaments, scientific societies; all were inventions of necessity, built to give structure to a conversation that had suddenly become too big for the old rules to hold.

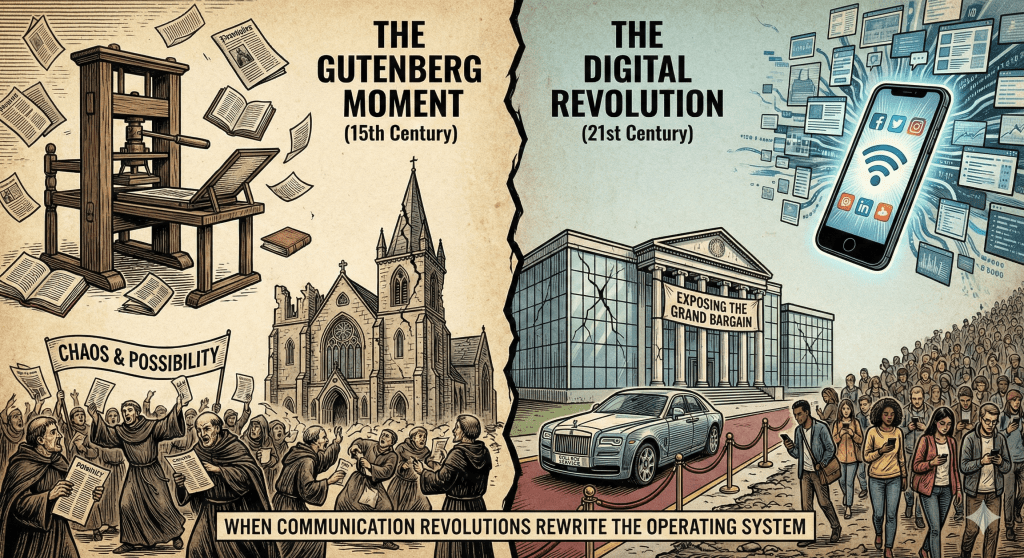

We’re living through our own Gutenberg moment now. The internet, the smartphone, and social media have again collapsed the gatekeepers of knowledge. Anyone can publish, broadcast, or mobilize. Everyone has a printing press in their pocket.

And just like the fifteenth century, the result isn’t a sudden leap into enlightenment; it’s a flood. A flood of voices, yes, but also of noise. Of certainty without understanding. The old institutions of coherence — newsrooms, universities, churches, governments — were built for a slower, more stable flow of information. They weren’t designed for the torrent we live in now, where attention moves faster than comprehension and trust erodes faster than truth can form.

We tell ourselves that this upheaval is new, but it follows an old pattern. Every communication revolution begins with a burst of freedom, followed by disorientation. The established order loses its grip before a new one takes shape. What we’re experiencing is not decline; it’s a transition. The chaos, the outrage, the mistrust of authority, the feeling that everything is coming apart: this is what it looks like when a culture’s operating system is being rewritten in real time.

As we live through our own Gutenberg moment, it’s worth remembering that the first one didn’t land on stable ground. When Gutenberg’s press spread across Europe, the Catholic Church — the institution that had held the continent’s social and moral order together for centuries — was already under strain. Corruption was rampant. Trust was fraying. People could see the gap between what the Church claimed to be and how it actually behaved. The printing press didn’t create that crisis of legitimacy; it exposed it. It gave people the means to see hypocrisy in print, to organize dissent, and to build new movements outside the old hierarchy.

That’s the real lesson of Gutenberg. The technology didn’t destroy the system; it revealed its rot and accelerated the change that was already underway. And that’s where the parallel to our own time begins. The internet, the smartphone, and social media didn’t create the divisions, distrust, and exhaustion of modern America. They just stripped away the illusion that our institutions were still strong enough to hold us together.

What gaps do people see in the legal profession between what we claim to be and how we have actually behaved? Richard Susskind identifies the violation of the Grand Bargain:

And one way to think about the grand bargain is as a metaphor for this arrangement that we have in place between the professions in society. And the central idea is that the professions are granted exclusivity, and in return for that exclusivity, there’s this expectation that they’ll make that practical expertise available and affordable in an accessible way, as I’ve said before. So that’s the grand bargain and it’s clearly in place in the legal profession. To answer your question of why has the legal profession failed, because the legal profession – and it’s not just the legal profession, it’s across the professions – they’re not upholding their side of the bargain. Most people in most organizations can not afford the services of first rate professionals or indeed any professionals. The expertise of legal professionals is a very, very scarce resource in society. We’ve built a Rolls Royce service for a few and everyone else seems to be walking.

Leave a comment